Toyohiko Kagawa was a great Japanese evangelist and social reformer. He came from a rich non-Christian family. He was born in 1888 and in the course of his education sought instruction in English from a Christian mission in the city of Tokushima. Luke’s Gospel was one of the books from which he was taught. He found the picture there of the love of Christ increasingly attractive.

Kagawa was eventually baptised, an event which brought disinheritance by his family. For about four years he attended a Presbyterian theological college in Kobe, during which time he became painfully aware of the appalling social conditions under which so many of his countrymen and women lived.

On Christmas Day 1909 he went to Shinkawa, a slum area of Kobe. There he lived in a room two metres square with no window. His daily food consisted of two bowls of rice gruel. Anything else given to him he gave away. He became the acknowledged guide and leader of the countless poor in that industrial city. He preached, taught and lived love, peace and social justice. “If we could learn to love one another,” he said, “it would be a solution to our problems.” But, he insisted, the way of love is the way of the cross. “The knowledge of the Love of God comes only by way of the Bloody Cross; he who fears to bear it cannot know the Love of Christ.”

In 1914, with help from some of the churches, he went to Princeton University in the United States of America, where he spent three years studying social problems. On his return to Japan in 1917 he devoted all his efforts to improving the conditions of the poor. He was on the government list of dangerous radicals, and for many years was watched constantly by the police. One of his major tasks was the formation of trade unions, which were at the time forbidden by Japanese law. This brought him into conflict with the authorities, and he was imprisoned in 1921 and again in 1922. Yet, when a huge earthquake levelled Yokohama and Tokyo in 1923, it was to Kagawa that the government turned to lead the work of reconstruction.

A pacifist from his youth, Kagawa founded the National Anti-War League in 1928, and was imprisoned again in 1940 because of an apology which he made to China for his country’s attack on it. During the Second World War he denounced both Japan and the Allies for their part in the conflict. Yet after its conclusion the government again sought his help in restoring the life of the nation, and he became a leader in Japanese moves towards democracy. Such was his fearlessness and strength of purpose, that when he was brought before the emperor he spent the whole time expounding the gospel of peace.

In the 1920s and 30s he was constantly involved in evangelism. He began the Kingdom-of-God Movement in 1930 and travelled extensively overseas to preach and teach. He became one of Japan’s outstanding writers both in fiction and religion. The claim of Christ upon his life, love and service was his guiding principle until his death on 23 April 1960.

The beginnings of the story of St George appear to lie in the region of Lydda, a town on the coast of Palestine, where a certain George was martyred about 304. That would make him one of the victims of the attack upon Christians made by the emperor Diocletian in the last and most severe period of persecution before the Christian faith was recognised by the state. Little else is known for sure about George. He was possibly a soldier. His name occurs in many of the early lists of martyrs, and his cult became widespread in the church. He was known in England by the seventh and eighth centuries, though the process by which he became patron saint of England is by no means clear.

The enormous popularity of St George in England seems to have grown up during the crusades. A vision of St George and St Demetrius preceded the fall of Antioch on the First Crusade, and Richard I placed himself and his army under the saint’s protection. According to tradition it was King Edward III who made St George patron of the Order of the Garter in 1348, and whose soldiers first raised the cry, “For England and St George”. Soldiers and sailors began to wear his red cross on a white ground as a sort of uniform. With Caxton’s printing of the Golden Legend in the next century, the saint’s story was widely read, in particular the famous episode of his vanquishing the dragon, a story that is probably no older than the twelfth century and possibly derived from the ancient story of Perseus slaying the sea monster.

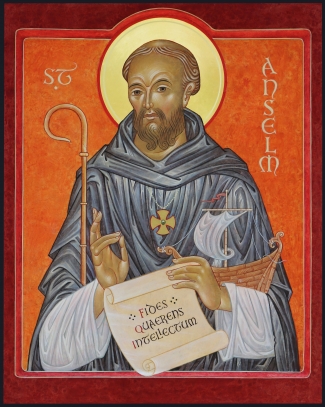

Anselm was born in 1033. After some years of undisciplined life he entered a monastic school in Normandy. In 1060, influenced by Lanfranc, prior of the abbey of Bec, Anselm took monastic vows. Three years later he succeeded Lanfranc as prior and in 1078 became the abbot of the monastery.

On a visit to England Anselm renewed his acquaintance with Lanfranc, who had become Archbishop of Canterbury. On Lanfranc’s death in 1089, Anselm was proposed to succeed him, but King William II would not at first consent. There was considerable conflict at the time over the respective powers of the monarch and the church with regard to appointments, responsibilities and accountability. Not only did it take until 1093 before Anselm was consecrated Archbishop of Canterbury, but he spent much of his episcopate in exile from England because of the strife first with King William II and then with Henry I over the issue. Despite the time and energy taken up by this conflict, Anselm succeeded in initiating far-reaching reforms in the church in England, including the holding of regular synods and a renewed emphasis on the celibacy of the clergy.

Anselm was by nature a scholar and a monk and devoted to prayer. He is best remembered for his theological work. He made a significant contribution to theology through his development of the so-called “ontological argument” for the existence of God: “God is that than which nothing greater can be conceived.” A thing existing in reality is greater than that same thing conceived of only in the mind; therefore God must truly exist.

Anselm also, in his most famous work, Cur Deus homo (Why God became human), gave classic expression to the “satisfaction theory” of Christ’s work. He explains it in terms of feudal society: when a vassal breaks his bond with his lord, satisfaction must be made. In our relation to God, we cannot make satisfaction because of our sinfulness, therefore God, in human perfection in Christ, offered satisfaction for our sin.

Behind Anselm’s scholarly theology lay a profound piety. He was less interested in “proving” God’s existence or explaining Christ’s work than in helping Christians give a coherent account of the faith by which they live. Faith and prayer always came first. In one of his early theological works he wrote:

I do not try, Lord, to attain your lofty heights, because my understanding is in no way equal to it. But I do desire to understand your truth a little, that truth that my heart believes and loves. For I do not seek to understand so that I may believe, but I believe so that I may understand. For I believe this also, that “unless I believe, I shall not understand.”

Anselm died in 1109.

8:00am Holy Communion (BCP)

10:00am Eucharist (ANZPB)

10:00am Zoom Service

5:00pm Taizé Service

Fisherfolk Newsletter & Pew Sheet

The Messenger

2023-2024 Lectionary Year B [PDF]

Church & Hall Hire

April 2024 Roster

Online Worship Resources

Past Sermons

St Peter's Blog

April 24 - Toyohiko Kagawa

April 24 - Daily Office

April 23 - St George of England

April 21 - Fourth Sunday of Easter

April 21 - St Anselm

April 14 - Third Sunday of Easter

229 Ruahine Street,

Palmerston North

Email: stpeters@inspire.net.nz

Phone: (06) 358 5403

Office Hours

Tuesday to Friday

9:00am to 12:00pm

Closed on Public Holidays