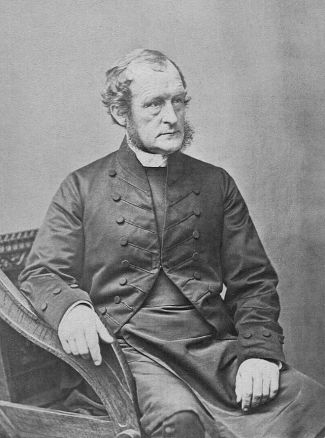

George Augustus Selwyn provided remarkable leadership for the church in New Zealand during the twenty-six years of his episcopate. His most enduring contribution was the first constitution of the Anglican Church in New Zealand. He was born in 1809 and was educated at Eton and St John’s College, Cambridge. He made friends there with many who were to prove extremely helpful in promoting his work in New Zealand. He was ordained deacon in 1833 and priest a year later and served as a curate at Windsor, a task he combined with tutoring duties at Eton. In 1839 he married Sarah Richardson. The Church of England was entering a period of turmoil over its place in the state and its role in national affairs. Selwyn developed high ideals of the autonomy of the church and of its responsibilities in society, especially in the field of education.

George Selwyn was appointed the first bishop of New Zealand when his brother William declined the position. He was consecrated bishop in October 1841. Selwyn saw that his role as a bishop was to lead the mission of the church. On arrival in New Zealand in 1842 he brought his exceptional energies to bear on organising the church. He made several strenuous tours of his vast diocese on foot, horseback, by canoe and ship. From 1847 he included the islands of Melanesia in his journeys.

Selwyn’s enthusiasm for education found expression in St John’s College. His vision encompassed a veritable educational empire, from pre-school to tertiary education for Maori and pakeha. The vision was clearly romantic and over-ambitious, though Selwyn’s dynamism made parts of the scheme work for a few years. The college was established first at the Church Missionary Society station at Waimate, but was moved to Auckland in 1844.

Selwyn had learned sufficient Maori on the voyage out to New Zealand to preach and converse a little in Maori on arrival. He shared the strengths and limitations of the nineteenth century humanitarian view of indigenous races. He had a deep affection for the Maori people and a strong sense of their worth and equality, though the equality meant the inculcation of “civilised” habits and traditions. In the conflicts of the 1860s, his commitment to justice for the Maori people in Taranaki infuriated many of the European settlers, but, equally, his acting as chaplain to the British troops lost him some Maori support. Selwyn was a vigorous and forceful leader of the church, and occasionally this led to tensions between him and some of his clergy, particularly the members of the Church Missionary Society, who were responsible to their own organisation as well as to Selwyn. Nevertheless, Selwyn worked with his clergy and called two synods to approve common policies for the church. With the establishment of other dioceses in New Zealand (Christchurch, 1856; Wellington, Nelson, and Waiapu, 1858), Selwyn’s diocesan work was confined to the Diocese of Auckland.

The most significant legacy of Selwyn to the church in New Zealand was its constitution. The Church of England with its state connections had no model to offer for church government, and Selwyn drew up a constitution on the lines of the episcopal churches in Scotland and America. Selwyn fostered support for his constitution in New Zealand. In its final form, as agreed to in 1857, it provided a basis for synodical government in three houses (bishops, clergy, laity) meeting in one chamber. The provision of a separate house of laity was a significant development in the role of the laity in church government. In 1867, while at the first Lambeth Conference, Selwyn reluctantly agreed to become bishop of Lichfield and moved there in 1868. He died at Lichfield in 1878. His grave is in the cathedral close, with a memorial inside the cathedral. His wife Sarah, who had patiently accompanied him to New Zealand and joined whole-heartedly in his work, died in 1907.

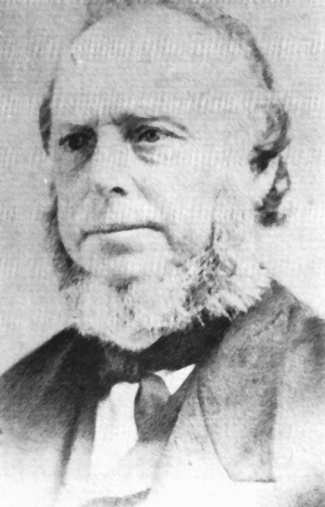

William Law was born in 1686 and educated at Emmanuel College, Cambridge. He was ordained deacon in 1711 and elected a fellow of his college in the same year. When George I came to the throne in 1715, Law refused to take the oath of allegiance and was deposed from his fellowship. He joined the Nonjurors - those who maintained that by the divine right of kings James II and his successors were the rightful kings of England.

Law was ordained priest in 1728, but, as a Nonjuror, could not hold any office in the Church of England. He became tutor to Edward Gibbon (who later became the father of the famous historian of the same name). In 1740 he retired to a semi-monastic household in King’s Cliffe, where he had been born. With the help of some friends he devoted himself to establishing schools and almshouses as an expression of the life of disciplined prayer that governed the household. There were prayers several times a day. They lived a simple, austere life and devoted their income to good works.

The book Law published in 1728, A Serious Call to a Devout and Holy Life, had a profound influence on many people, including Samuel Johnson and John and Charles Wesley. Its title well illustrates the main theme of much of his writing. He stresses the exercise of Christian moral virtues and personal discipline. In so doing, he provided an important stimulus to the development of the characteristic spirituality of the evangelical revival. The work reflects Law’s own sombre character and his meticulous attention to rules for personal conduct. In an age of conventional church-going, Law inculcated personal religion of the highest standards. He reacted strongly against easy-going Christianity and all attempts to compromise with the world. He launched a somewhat bigoted attack on the theatre and regarded the sins of “the world” as more dangerous than those of “the flesh” and “the devil”.

Law’s later works show the influence of the German mystic, Jakob Boehme. In his Spirit of Prayer (1749) and The Spirit of Love (1754), Law explored the inner foundations of religious experience. In an age when reason was widely regarded as the key to life’s mysteries, Law came to distrust reason. Law found feeling and emotion better keys to life. In the spiritual life, the indwelling of Christ in the soul was of paramount importance. This mystical element led to a degree of estrangement between Law and the evangelicals.

William Law died in 1761.

Dietrich Bonhoeffer was born in 1906 in Breslau, Germany. He was brought up in a tradition of Christian humanitarianism and liberalism, and quickly developed a great love for life. He studied theology at Tübingen and then Berlin. In 1928 he went as a curate to Barcelona for a year, and then in 1930 became a lecturer in systematic theology in the University of Berlin. A brilliant career as an academic theologian lay ahead of him.

All of this changed when Hitler came to power in 1933. Bonhoeffer regarded National Socialism as an attempt to make history without God. He publicly denounced the political system which seemed to him to make Hitler its idol and god, and resigned his post at the university. He became part of the Confessing Church, those within the German churches who set the sovereignty of Christ above all other loyalties, in particular any loyalty to Adolf Hitler.

Bonhoeffer left Germany for London, where he served as a chaplain to the Lutheran congregation and became deeply involved in the ecumenical movement. When he returned to Germany in 1935 he was forbidden to preach, teach or even enter Berlin. So he went to the Confessing Church’s training college on the Baltic coast and directed this until it was closed by the government.

Bonhoeffer wrote a number of important works in which he discussed the form of Christianity in an increasingly secular world. Although sometimes described as an advocate of “religionless Christianity”, Bonhoeffer’s real concerns were with the sense of the ultimate in the midst of life and with speaking in a secular way about God. He sought a Christianity freed from the strictures of traditional religion.

When war came in 1939 Bonhoeffer was in America, but it soon became clear to him that he must return to his own country to be with his oppressed and persecuted fellow Christians: “I shall have no right to participate in the reconstruction of Christian life in Germany after the war if I do not share the trials of this time with my people.”

Bonhoeffer inevitably became involved with the political underground movement, and in April 1943 was arrested by the Gestapo. At first he was held in prison in Berlin, but at the beginning of 1945 he was transferred to Buchenwald. In prison at Buchenwald he devoted his life to ministering to his fellow prisoners. He inspired many, including some of his guards, by his courage and unselfishness. It has been said that in those terrible and frightening conditions he stood like a giant before men. Behind all this lay his faith in and love of God, to which his poems and writings smuggled out of prison bear eloquent testimony:

Discipleship means allegiance to the suffering Christ, and it is therefore not at all surprising that Christians should be called upon to suffer. In fact it is a joy and a privilege, and a token of his grace.

On 9 April 1945, by order of Himmler, Dietrich Bonhoeffer was executed at the concentration camp at Flossenbürg, a few days before it was liberated by the Allies.

Normally observed on 25 March, this year the Feast of the Annunciation has been displaced by Easter week and is thus transferred to 8 April.

Respect and honour have been shown to Mary as the mother of Jesus from early in the church’s history. The Feast of the Annunciation (Lady Day) focuses on one particular episode related to the vocation of Mary.

The observance of the feast appears to have emerged out of the late fourth and early fifth century debates over the person of Christ. It became widely observed soon after in the east and by the eighth century in the west. The church affirmed Christ’s full humanity as well as his full divinity. Christ’s oneness with our humanity is reflected in the exaltation of the role of Mary. In the controversies of the late fourth century she was affirmed as the “Mother of God”. The Annunciation is related to Christmas, which itself only began to be celebrated and find a fixed date on 25 December from the fourth century. The Annunciation is celebrated nine months before, on 25 March.

The Annunciation commemorates the event in Luke’s Gospel in which the angel Gabriel comes to Mary with the message that she is to bear a son (Luke 1:26-38). In telling Mary this, Gabriel also points to some key images by which Jesus is to be understood. He will be “Son of the Most High”; he will be the descendant of David who will reign for ever; he will be “Son of God”.

In Luke’s careful telling of the story there are strong parallels between the annunciation to Mary and the earlier annunciation to Zechariah of the birth of John the Baptist (Luke 1:18-20). Both stories show strong echoes of the story of Abraham and Sarah and the birth of Isaac (Genesis 18:1-15, 21:1-7) and of the story of Hannah and the birth of Samuel (1 Samuel 1:1-20). Mary is portrayed as the faithful and obedient servant of God who has found favour with God.

8:00am Holy Communion (BCP)

10:00am Eucharist (ANZPB)

10:00am Zoom Service

Fisherfolk Newsletter & Pew Sheet

The Messenger

2023-2024 Lectionary Year B [PDF]

Church & Hall Hire

April 2024 Roster

Online Worship Resources

Past Sermons

St Peter's Blog

April 20 - Daily Office

April 14 - Third Sunday of Easter

April 11 - George Augustus Selwyn

April 10 - William Law

April 9 - Dietrich Bonhoeffer

April 8 - The Annunciation

April 7 - Second Sunday of Easter

229 Ruahine Street,

Palmerston North

Email: stpeters@inspire.net.nz

Phone: (06) 358 5403

Office Hours

Tuesday to Friday

9:00am to 12:00pm

Closed on Public Holidays